SYNCHRONICTY

Tuesday, March 13, 2012

Teufelsberg Test Post

Nevertheless, as with any other comparableurban

renewal projects, these efforts might not be reducing inequality. I

wouldargue that social tensions are fewer in Marseille than in any other

French citybecause of its socio-spatial structure. On a recent visit to

Marseille I couldwitness that on the one hand the social housing blocks

are spread all over thecity, be it in the centre or further out. On the

other hand, what is also verydistinctive and different from other

cities is that these blocks are notsurrounded by a ill-defined semi-or

quasi-public space usually in the form of a poorly maintained lawn, but

theyare interlocked with the surrounding urban fabric. Therefore their

ground levelcreates urban qualities that tower-on-the-lawn-typologies

are not able tomaintain. Hence, these structures enhance an integration

of less-affluentpopulation in the inn

Monday, March 12, 2012

Marseille La Rouviere

Websites are crucial for business and for those who make their living online. For a guy like me, all my blogs need to be monitored for downtime regularly. Since everybody knows its impossible to keep track of website downtime manually, website monitoring tools alert us through email or SMS when your website or blog goes down.

Thursday, March 8, 2012

Marseille – An Integrative Model for Inner-City Social Housing?

Unlike other French cities, Marseille’s socio-spatialstructure is distinctively different from a prevailing concentriccentre-banlieue urban landscape with outwardly growing poverty, crime, andsocial segregation. Might this specific socio-spatial distribution be a modelto diminish social tensions?

For years, especially up to the late 1970s, the city hasstruggled with frictions and inequalities that frequently have erupted inviolent riots, mainly due to the cities heterogeneous population structure. Inless then a decade, the city lost around 10% of its population throughmigration to suburbs and other cities in the Provence as a direct result ofuncontrolled violence. For years the control of violence and crime has been atop agenda for Marseille’s ruling politicians. Astonishingly, violent riots intheir grand ensembles in the last years were few compared to the rest of thecountry’s big cities. Reasons for this might be manifold.

In the hometown of Corbusier’s famous firstmachine forliving the geographical situation as the closest harbour for North-African immigrationcaused high demands in housing supplies. Therefore, and also as a consequenceof vast bombings during WW II, numerous grands ensembles (housingestates) and housing blocks had to be erected in the city in the second half ofthe 20th century. As a result the whole cityscape is interspersedwith huge concrete estates and tower blocks.

|

| View on Old Harbour (left) and the Belsunce district. Image by SYNCHRONICITY |

Local politics argues that one limitingeffect on further street riots might be the fact that the city’s economy issteadily growing since the 1990s and new industries settle down in theMediterranean harbour city. Furthermore the government is undertaking hugeinvestments in regeneration projects and new developments such as the huge EuroMéditerranée project. Thelater involves regenerating previously derelict parts of the inner city inducingprocessesof gentrification and erecting a new seaside district close to the oldharbour. Thereby the city is following a well-known script of large-scale urbanregeneration: ‘building a city within a city’, establishing a multifunctionalnew quarter with offices, homes, commerce, recreational and culturalfacilities. Thereby they are relying on expressive architectures by well-knownarchitects such as Fuksas,Hadid,Nouvel,and Boeri.

Nevertheless, as with any other comparableurban renewal projects, these efforts might not be reducing inequality. I wouldargue that social tensions are fewer in Marseille than in any other French citybecause of its socio-spatial structure. On a recent visit to Marseille I couldwitness that on the one hand the social housing blocks are spread all over thecity, be it in the centre or further out. On the other hand, what is also verydistinctive and different from other cities is that these blocks are notsurrounded by a ill-defined semi-or quasi-public space usually in the form of a poorly maintained lawn, but theyare interlocked with the surrounding urban fabric. Therefore their ground levelcreates urban qualities that tower-on-the-lawn-typologies are not able tomaintain. Hence, these structures enhance an integration of less-affluentpopulation in the inner city districts not only through their distribution butalso through their ground-level integration. Arguably the Marseille example, might be a model to overcomethe prevalent structures of ghettoizing the poor on the city’s fringes andallows for a more heterogeneous socio-spatial distribution that consequentlyalso reduces social tensions.

|

| Inner-city social housing in the Belsunce district with activated ground level. Image by SYNCHRONICITY |

Labels:

Marseille,

SPATIALITIES,

URBANITIES

Wednesday, February 22, 2012

Everyday Creativity – Community Gardens at Tempelhof Airport in Winter

A recent winter walk at the former airfieldof Tempelhof Airport in Berlin also took me to the Allmede-Kontorplot where community gardens are located between the former runways. At thesnow-covered airfield urban garding obviously has come to a halt. But thecreatively and tenderly assembled nests of the community gardeners wait to be re-cultivated in spring, which is hopefully soon to come.

Meanwhile I’d like to share these pictures asexamples of everyday creativity. These spaces ofvernacular creativity are examples that emphasise the role for non-economicand non-productive values and practices in shaping processes of urbancreativity. They foster a rethinking of the ‘Creative Class’, aterminology that usually does not encompass these kinds of spaces who arecreated by local residents of any classes.

| all images by SYNCHRONICITY |

Labels:

creative city,

SPATIALITIES,

urban agriculture,

URBANITIES

Friday, February 17, 2012

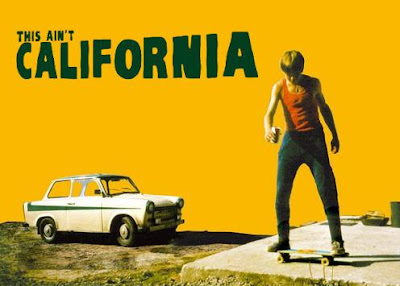

This Ain’t California – Skateboarding and the City in the GDR

|

| Skateboarding at Alexanderplatz. Film still ‘This Ain’t California’ |

The German documentary ‘This Ain’t California’ by MartenPersiel, which premiered a few days ago at the BerlinaleFilm Festival is an impressive document of skateboard culture in the GDR andalso got me thinking about public space in GDR Berlin. The director brought togethera former GDR 1980s skateboard gang, whose members vividly reminisce about howthey built their first Rollbrett andlater smuggled skateboards from the West to the East and how the skateboardingscene grew in the GDR. The terrific film sets the subculture of skateboardingin the context of the political landscape of that time. At a time when the Eastern bloc alreadystarted to crumble, a vivid skater culture, partly autonomous partly withWestern influence developed. The concrete desert of East Berlin’sAlexanderplatz was on the one hand the most obvious stage for the skaters onthe other hand also a site of subverting the authoritative socialiststate. The public space no longerwas a means of representation or intimidation, through skateboarding it got aplace for self expression and if not intentionally also for resistance.

|

| Skateboarding at Alexanderplatz. Film stills ‘This Ain’t California’ |

In the GDR, sport was highly reputable andpromoted. Especially top-athletes, and the GDR had many of them, were highlyrespected as representatives of their state. But skateboarding was not such asport, since it was seen as a pop-cultural capitalist threat invading from theWest. Therefore, as the documentary depicts, the skateboarders where surveyedby the Stasi as potential dissident citizens. Simultaneously authorities triedto control the teenagers through the installation of institutionalisedfacilities to train and coach this new sport to make the GDR also competitivein international skateboarding events. Obviously these institutions were neverreally successful amongst the skateboarders, as also in the GDR the sport wasmore understood as a way of life rather than a sporting discipline.

Arguably, the act of skateboardingquestioned the state of public spaces of the socialist regime. Skateboarding,or in GDR terminology Rollbrettfahren,was a form of embodied resistance and rendered the space as a representationalspace. As the documentary clearly elucidates, not only in the West but also inthe East skateboarding was built on an anarchist tradition of hacking the urbanlandscape. Iain Borden (authorof Skatebordingspace and the city: architecture and the body) argues in a Lefebvrian sensethat ‘skateboarders see the city as a place to assert use values over exchangevalues, pleasure over toil, active bodies over passive behaviours’. In otherwords, skateboarders communicate a Marxist approach that public space is foruses rather than exchange. In this sense, in a way, skateboarding would havebeen a spatial practice that was in conformity with socialist ideologies. Butin former Eastern Germany there was no such thing as a capitalist abstractspace the skateboarders could challenge with their activity, as public spacewas never a space of consumption. Nevertheless skateboarding as depicted in‘This Ain’t California’ was an implicit critique of what public space shouldbe, a critique that was true for both the East and the West.

Apart from raising questions about publicspace the documentary is a highly recommendable and entertaining film thatcomments on GDR politics, youth culture and everyday life through an impressiveamount of original footage. Of course, the film also resonates with a certainnostalgia for old school skateboarding and in general for GDR aesthetics, so called Ostalgie.

|

| Skateboarding in East Berlin, Thrasher Magazine, December 1988 |

|

| Skateboarding at Alexanderplatz. Film stills ‘This Ain’t California’ |

Labels:

film,

public space,

SPATIALITIES,

URBANITIES

Wednesday, February 8, 2012

Double Fake - Imitations at Berlin Potsdamer Platz

At times of the Berlinale film festival,one heads out to Berlin Potsdamer Platz quite frequently. I recently took acouple of pictures of the remains of the potemkin village in the heart ofBerlin's inner city.

The Potsdamer Platz and its adjacent Leipziger Platz, gotrebuilt as the new (old) downtown city center according to local urbanplanners. In order to not be too dependent on investment the city decided tobuild fake buildings instead: Huge scaffoldings dressed in banners withfacade printing anticipate what once will be. The last remaining giant is thescaffolding separating Leipziger Platz from Potsdamer Platz. Together with itstwin (an actual building) they articulate a symmetric gate seen from the oneside, and enclose the octagon of Leipziger Platz from the other side. The areagot completely destroyed during the bombings of WW II; after the Wende, Leipziger Platz got restored inplan. However many of the new buildings are reminiscent of the 1920s era. Therefore,with its huge buildings and high-rises, this part of the New Berlin imitatesNorth American downtowns such as New York or Chicago. Like in other parts of the city, current urban planning tries to imitate the image of the GoldenTwenties when Berlin was the flourishing, densely populated capital of WeimarRepublic. Only 1920sBerlin never looked like 1920s New York. Arguably the contemporary PotsdamerPlatz has an aura of a double fake: buildings that are not buildings, and new buildingsthat pretend to be old. These are conspicuous symptoms of both, the citystruggling with its past and the image the contemporary metropolis aspires tocreate.

| The building and its fake twin. 2012. (Image by SYNCHRONICITY) |

| Fake building. 2012. (Image by SYNCHRONICITY) |

| (Image by SYNCHRONICITY) |

|

| Leipziger Platz scaffolding 2010 (Image source) |

|

| Leipziger Platz / Potsdamer Platz 1902 (Image source) |

|

| Leipziger Platz 1921 (Image source) |

|

| Leipziger Platz 2011 with two fake buildings (Image source) |

|

| 1920s inspired architecture at Potsdamer Platz (Ritz Carlton) Image source |

|

| Scaffolding on Google Maps |

Labels:

berlin,

SPATIALITIES,

URBANITIES

Thursday, February 2, 2012

Anagram Urbanism - Re-shuffling the City

|

| Jellyfish Theatre London 2010 (image source) |

Conceptually, they understand their work asa snapshot of recycling and reshuffling a city's materials and thereforeemploying the concept of an anagram. I would argue further to not onlyunderstand their way of reshuffling materials as being analogous to theanagram, but also the fact that many of their constructions are executed in acollective effort to integrate local inhabitants in the process of building:'Beyond creating art and design objects and architecture, we initiate action'.Hence, through a participatory approach and the way in which a city's materialsget recycled and reshuffled the whole process might be termed as AnagramUrbanism: Reshuffling and recycling the built and human fabric of the city.Thinking this further, such a conceptualisation of an urbanistic approachpresupposes that the ingredients for urban change are already inscribed in thecity itself; the actions that need to be taken are excavating this pre-existingpotentials lying within the urban human and nonhuman networks and initiatingand orchestrating a process of reshuffling. The Anagram Urbanism approach wouldthen be in close dialogue with Saskia Sassen's work on OpenSource Urbanism which has been recently presented here on this blog. Discoveringthe pre-existing potentials or utilising the existing recources inscribed in the city, Anagram Urbanism then is comparable to Sassen'sunderstanding of the city as incomplete and the potential of the city to 'talkback'. And to go further, would that mean that the approach of an Anagram Urbanism wouldmake our cities more resilient, environmentally and also socially? I am not able to give the answers yet but I believe that this conceptual framework is definitively helpful to think about the present and also future state of the city and, furthermore also bears the potential of being incorporated into urban planning strategies.

To finish this thought, here are some images ofKöbberling/Kaltwassers work, that, in case you have not recognised yet, is alsofeatured as the new header image on top of the blog.

Labels:

header,

Open Source Urbanism,

Participation,

SPATIALITIES,

URBANITIES

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)